The Bitten Peach and the Cut Sleeve

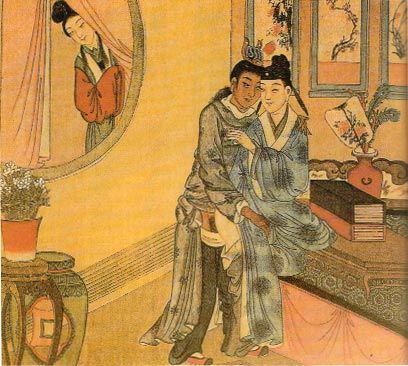

A painting of a woman spying on two men having sex. The piece is from the Qing Dynasty.

Content warning for suicide

"Favors of the cut sleeve are generous. Love of the half-eaten peach never dies,"

– Liu Zun

Two of the most famous gay couples in Chinese history are also the sources of some of the most recognizable queer symbols in China: the bitten peach and the torn sleeve. Stories that are partially legend, partially based in some reality, have expanded beyond what anyone could have imagined and shifted from a romanticized look at a homosexual romance to a term to be clung to as a historical hook from past to present; a reminder that there is a precedent for the kind of queer love that continues in contemporary China, despite attempts to stamp it out.

The first story begins with a Duke and a courtesan; their relationship continued from 493-534 BC. As the story goes, Duke Ling, a married man, was madly in love with his courtesan, Mizi Xia. Mizi Xia was said to be incredibly beautiful and well-loved throughout Wie, the land the Duke ruled. While the two were in an extramarital relationship, the Duke was very open about his love for the other man. He was known for bragging about Mizi Xia when the two were still close, and that fact alone tells us a lot about queer relationships at that time. It was tolerated that the Duke had an extramarital affair with a male courtesan. He was allowed to not only brag about the relationship but also give his lover favours.

The first began when Xia's mother became ill. Xia, upon receiving the news, forged the Duke's signature to take one of the carriages. This offence was punishable by cutting off the thief's feet, but when Xia returned, the Duke didn't punish him. Instead, he praised his love's loyalty to family and willingness to face punishment to be with his mother.

Another source of pride for the Duke was the bitten peach; a symbol still used to signify love between men in China. While walking through the garden together, Xia picked a peach and took a single bite. When he realized it was particularly sweet, he gave it to the Duke. The Duke praised Xia, saying:

"How sincere is your love for me! You forgot your appetite and thought only of giving me good things to eat!”

It is a beautiful story, but its telling begins for another reason. It was originally recorded by a scholar who used the story's beginning and eventual end as a parable. It was said that after Xia's beauty faded, so did the Duke's love for him. He was accused of crimes against the Duke—the crimes for which he'd received praise. The theft of the carriage and the gift of the half-eaten peach, once hailed by the Duke, now brought punishment for Xia. The scholar used the Duke's shifting attitude to ward against the dangers of falling into the favour of powerful people.

The second story involves higher stations and higher stakes: Emperor Ai of Han and the commander of his armed forces, Dong Xian. The Emperor was known for his sentimentality in connection with awarding stations; having four dowager empresses simultaneously, a feat that he was the first and last to manage. Still, there were harsh consequences, as warned by Prime Minister Wang Jia. He cited the many other people close to the emperor who had been promoted quickly and faced punishment for that.

The Emperor reacted by accusing the Prime Minister of false crimes and forcing him to commit suicide. He reacted to all criticism of his lover in this fashion and spent his life very in love with the Xian. Unlike the Duke’s relationship with the courtesan, the Emperor did not turn against his lover. By all accounts, he spent his life entirely in love with the man, leading to the story of the cut sleeve.

On one occasion, Dong Xian fell asleep in the emperor’s arms. When the emperor had to leave, he cut off his sleeve so as not to wake his love. Again, the story was simple, small, and very sweet, but it had an untold conclusion. When the Emperor died, so did Dong Xian, though not for the same reason. While the Emperor died of natural causes, Dong Xian committed suicide. The Emperor ordered Dong Xian to be given the throne after his death, but the order was ignored the minute his body was cold. All of Dong Xian’s titles were stripped away, and he killed himself, along with his wife. After his death, people around the land cut their sleeves to honour him as a symbol of mourning and respect.

These two stories have many common factors: small gestures of affection, gentle sacrifices, and the love of two people from wildly different stations. They have also grown and spread throughout the world. Not only used by queer people in China to communicate with each other but by people of Chinese descent who live outside of China, they are able to connect with and expand on the queer history of a country that has a government that is largely hostile towards queer relationships. In a country where even discussion of queerness is censored, the language queer people use to speak to each other is significant and worth preserving wherever possible. The history of these terms matters, but history is still being made by them.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Editorial Board. (2000). Chinese Tradition of Male Love [Abstract]. Retrieved from http://www.gay-art-history.org/gay-history/gay-customs/china-gay-cut-sleeve/china-homosexual-bitten-peach.html

Gil, V. E. (1992). The cut sleeve revisited: A brief ethnographic interview with a male homosexual in mainland China.

Hay, B. (n.d.) Comrades of the Cut Sleeve Homosexuality in China [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://bobhay.org/_downloads/_homo/11%20Comrades%20of%20%20the%20Cut%20Sleeve.pdf

Hinsch, B. (1990). Passions of the cut sleeve: The male homosexual tradition in China. Univ of California Press.

Shane, K. (2009). Pleasures of the Bitten Peach: An Exploration of Gender & Sexuality in Late Imperial China.

Sun, Z. (2010). Speaking out and spacemaking. Gender Equality, Citizenship and Human Rights: Controversies and Challenges in China and the Nordic Countries.

THE BITTEN PEACH: DECOLONIZING QUEER ASIANS. (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.aact.community/experience/open-call-the-bitten-peach-decolonizing-queer-asians

Wei, W. (2007). ‘Wandering men’ no longer wander around: the production and transformation of local homosexual identities in contemporary Chengdu, China. Inter‐Asia Cultural Studies, 8(4), 572-588.