The Golden Orchid Society

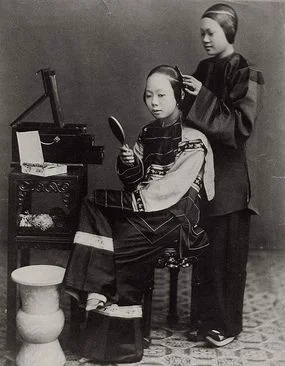

A Chinese woman does another Chinese woman's hair while she watches with a hand mirror.

"[Within the sisterhood], if two women have intentions towards each other, one of them would prepare peanut candy, dates and other goods as a gift to show her intent. If the other woman accepts the gift, she is now bound by honor to her suitor. If she refuses the gift, it is a rejection of the proposal. A contract-signing ceremony follows the acceptance. Those with the financial resources would invite their friends who come in droves to congratulate the couple and celebrate by drinking through the night."

– Hu Pu'an

The Golden Orchid Society was a collection of organizations in South China that began during the Qing dynasty and existed from approximately 1644 to 1949 when they were banned because they were associated with an attempt to overthrow the Manchu Emperor. Over 300 years, however, they created an order of women who stood in solidarity with other women against heterosexual marriages that were oppressive at best and far too often abusive. While some of the women may have been heterosexual and avoided marriage for reasons unrelated to their sexuality, the association clearly made a space for members who were lesbians or bisexuals. Queer women found the safety and family in the Golden Orchid Society that their biological relatives had often never provided them.

The culture of marriage in China before the Golden Orchid Society's existence was not wildly different from many other cultures' views on marriage. If a family had a cisgender daughter, their best option was to find a man to marry, hoping they could raise their station and profit from the marriage. A cisgender woman’s accomplishments were not considered important unless they attracted a potential husband or helped the family.

Once this woman was married, she was to do as her husband said and hopefully produce a son for him. For women who were attracted exclusively to other women, this was not a tempting option. Many women, heterosexual or otherwise, were not pleased with the idea of marrying men they weren’t attracted to.

The Golden Orchid Society provided something unique: other options. The first option was to get married to another woman. While these marriages were not always romantic or sexual, they had a similar courtship ritual as many heterosexual couples in China did at that time:

"[Within the sisterhood], if two women have intentions towards each other, one of them would prepare peanut candy, dates and other goods as a gift to show her intent. If the other woman accepts the gift, she is now bound by honor to her suitor. If she refuses the gift, it is a rejection of the proposal. A contract-signing ceremony follows the acceptance. Those with the financial resources would invite their friends who come in droves to congratulate the couple and celebrate by drinking through the night."

– Hu Pu'an, "A Record of China's Customs: Guangdong.”

That is not to say, though, that the practice was completely supported by society. It was still expected for women to marry men, and when they instead formed a union with another woman, it was seen as an act of rebellion. Often, despite a family’s disapproval of these same-sex marriages, they were forced into accepting their daughter’s decision. The alternative was a practice in the Golden Orchid Society where, when a woman was betrothed to a man without her consent, she was to reject all of his advances on the wedding night.

If the men tried to force themselves on the women, the women often defended themselves physically, thus breaching the terms of the marriage contract. Brides who did this were generally sent home as rejected wives, which made them virtually unweddable – to men, that is.

So when a woman proposed to the rejected wife, the families were often more open to the concept, as it would save them from the societal shame of having an unmarried daughter who had been rejected by her husband and freed them from financial responsibility for her. These marriages could happen in the first place because of the silk industry growing and giving women jobs. Two women could be financially independent, so many families found no reason to object and happily accepted their new daughter-in-law.

While it was rebellious to choose to marry another woman, that didn’t mean society didn’t accept it or disallowed them to be families. It was completely acceptable for same-sex couples to adopt and raise a daughter. Unlike those who were the product of relationships outside of the Golden Orchid Society, their children were allowed to inherit property.

That is not to say, of course, that the Golden Orchid associations were perfect. If a woman broke the oath of marriage by engaging in a heterosexual relationship, she would be publicly shamed and often beaten. And though at the time in China, while it was accepted for transgender women to present as they wished in some spaces, it was seen as a practice and not an identity. They were not considered women and were not included as members of the Golden Orchid Society.

They did make another step towards progress, a step that many members of the queer community still struggle with, specifically in the inclusion of aromantic and asexual individuals within the queer community.

When women in China were married, they would have their hair combed differently to signal to society and any men interested in courting them that they were not available. While the terms asexual and aromantic in their current meaning did not exist yet, the Golden Orchid Society had a system set up for women who wanted to avoid both marriage options, and any romantic or sexual partnership, by introducing “self-combing women.” These women would comb their hair into a married woman’s style and often had a ceremony to celebrate such a decision, similar to a marriage ceremony. And for asexual women who were romantically attracted to other women, the marriages were often non-sexual – a decision supported by most of the Golden Orchid Society.

These solutions were not perfect, though; if a woman, after making this oath, were to engage in a sexual or romantic partnership, she would face the same consequence that women married to other women would have if they had a relationship with a man.

The queer community, as it stands, still has a lot of growing to do. Many branches of the queer community respond aggressively to the less well-known communities of aromantic and asexual people.

A society that grew into the purpose of protecting women learned that it must protect more than one type of woman. Today, as parts of feminism ignore the struggles of queer women and much of the queer community ignores the struggles of the asexual and aromantic community, there is much that can be learned from the Golden Orchid Society. There is much to learn from history. Usually, when that is said, it means to learn from past mistakes. In this case, however, it is possible to learn from successes.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

The Tradition of Female-Female Unions. Cultural China. Retrieved from http://traditions.cultural-china.com/en/214T11933T14609.html

Thorp, B and Bullock, P. (2012, February 5). Lesbian Mothers of The Golden Orchid Society. Retrieved from http://www.towleroad.com/2012/02/lesbian-mothers-of-the-golden-orchid-society/