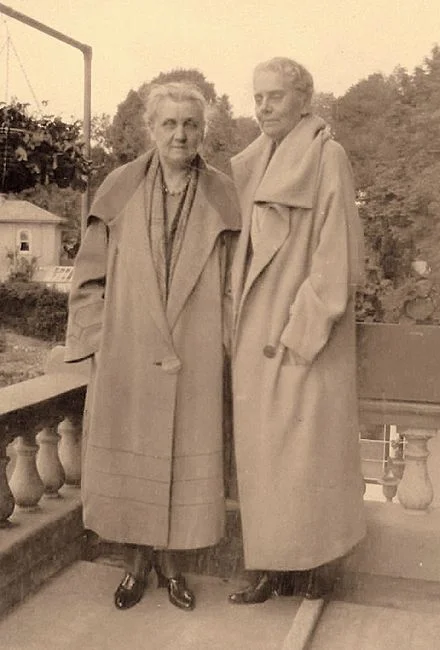

A browning photo of two white women standing next to each other. They are both wearing large coats.

"Mary Smith became and always remained the highest and clearest note in the music that was Jane Addams' personal life." — Victoria Bissell Brown, The Education of Jane Addams

Historians erasing queerness from the narrative isn’t new. Jane Addams’ story has gone another way; her queerness is known, and cannot be erased. Without it, her legacy would not exist in the same way. Instead, scholars and historians have attempted to use her work to overshadow her queerness while claiming the opposite was happening. Acknowledging one part of her life does not erase another; we must look at all the parts of her life to understand who she is and why she lived the life she did.

Born in the midwestern United States in 1860, Jane Addams was the youngest of eight children, though only four lived very long. She was born into a prosperous, political family with roots back to colonial New England. Jane spent the earliest parts of her childhood adventuring outside or reading for hours. She contracted Pott's disease when she was young, causing lifelong health problems and a permanent curve to her spine. This may have been one of the many things that influenced her work later in her life.

Jane was very close with her father; she wrote fondly of him in her memoir, and his opinions influenced her heavily. After becoming ill, she worried about walking with her father on Sundays, afraid she would embarrass him. He never pushed her away, and in fact, encouraged her to pursue higher education. Jane had big dreams of doing something useful for the world. Inspired by her mother's kindness and the works of Dickens, she decided to become a doctor.

Despite his encouragement, her father insisted she attend a nearby school. Though she dreamed of attending Smith College, she earned her collegiate certificate at a nearby seminary. The following summer, her father died unexpectedly, leaving each of his children with what would today be $1.27 million. In the fall, she moved to Pennsylvania with her sister Alice, her brother-in-law Harry, and her stepmother Anna in order to attend the Woman's Medical College of Philadelphia. Jane and Alice completed their first year, but Jane's health problems, a spinal operation, and a nervous breakdown stopped Jane from completing her degree. Her stepmother soon fell ill as well, and the family moved home to Ohio.

After further surgery and some familial encouragement, Jane travelled for several years and finally decided she could help people without becoming a doctor. The joyous epiphany was short-lived, and she once again fell into a depression, lost for a plan of action and distraught at the life expected of her. She spent much of her time reading and writing letters to her darling, Ellen Gates Starr. She had met Ellen at school, and the two were partners for many years. She talked with Ellen about Christianity and books, but mostly she talked about her hopelessness. Ellen later said that she felt closer with Jane when they were apart, sending letters, than when they were together.

Through their letters and her own readings, Jane learned more about the ideas of Christianity and social democracy, but she also learned how uneasy she was about the expectations of women to marry and raise a family. In the summer of 1886, she was baptized. The next summer, she read an article about settlement houses, and she had another epiphany. She decided she had to visit Toynbee Hall in London, the very first settlement house. Of course, she brought along Ellen. After several months in Europe, she still dreamed of starting her own settlement house but had taken no further steps. She had kept her idea a secret, and hoped telling someone would force her to take the next step. She finally shared her dream with Ellen, and she immediately agreed to help Jane make it happen. The result: Hull House.

The couple settled Hull House in September of 1889. At first, Jane paid for the work to be done on the formerly rundown mansion. Soon after, donations poured in from upper and middle-class women. Jane actually called upon women, especially those with the time, money, and energy, to get involved in the community as a form of "civic housekeeping." Hull House quickly became a home of social, educational, and artistic programs and a center for social reform. It was a place for immigrants and women especially—Jane Addams and Ellen Starr campaigned and promoted education, autonomy, and the destruction of traditionally male-dominated fields.

Upon settling Hull House, Starr and Addams had developed three "ethical principles" for social settlements: "to teach by example, to practice cooperation, and to practice social democracy, that is, egalitarian, or democratic, social relations across class lines.” Unfortunately, ethics are subjective. Addams’ construction of womanhood involved daughterhood, wifehood, motherhood, and sexuality. She believed that "social ills" very much included sex work. She believed that sexuality of all kind was at least somewhat immoral; despite her lifelong relationships with women, she remained celibate. Whether this is due to her morals which said sexuality was wrong or she was asexual, we cannot say.

The fact that Hull House existed in a poor neighbourhood wasn’t an accident. From her time at Toynbee Hall, Addams was most amazed at the sincerity of it; she dreamed of different social classes coming together. Settlement houses, as she had seen them, were spaces where connections could be made without being limited to the same class or background. Hull House offered classes in literature, art, history, current issues, and more. All were free, and they drew in working-class folks from not only the neighbourhood housing Hull House, but surrounding neighbourhoods as well. Jane didn't just create programs; she worked with the community and led surveys and studies on the causes of poverty, the needs of the community, and the issues they were facing. The results were shared openly with the community and used to push legislatures for social reform.

Jane Addams spent a good portion of her time with other lesbians or women who would most likely identify as lesbians today. Even later in her work with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, of which she was a founding member, she worked almost exclusively with other lesbians. Lesbians at the time and even today have lower income than their straight counterparts. They didn't have the benefit of a man's income, and women were discouraged from working. Jane fought against that wholeheartedly with her classes and push for reform. Because of this, Hull House was also a meeting spot for lesbians at the time. She believed that women were not only capable of doing men's’ jobs, but they were better suited. Addams led the "garbage wars"; in 1894 she became the first woman appointed as sanitary inspector of Chicago's 19th Ward. With the help of the Hull-House Women's Club, within a year over 1000 health department violations were reported to the city council. Garbage collection reduced the amount of death and disease.

A few years into Hull House, Jane grew close to one of the original donors of Hull House, Mary Rozet Smith. She had known Mary nearly since the opening of Hull House, but they began to spend more time together as Jane and Ellen grew apart. Victoria Bissell Brown wrote about Ellen, saying, "She was full of longing, as well, for a time past, a time “lost,” when friendship with Jane had been independent of any physical tie when they did not live together and seldom even saw each other." Ellen could not, and would not, compete with Hull House for Jane’s attention. Though she continued to do work through Hull House, their relationship wilted. On the other hand, Jane and Mary continued growing closer. Eventually, the two moved in together. Jane often expressed her love for Mary through terms of endearment, calling her “My Ever Dear” and “My Dearest One.”

Jane and Mary lived together, still very much in love, for forty years. They only parted when, in 1934, Mary contracted pneumonia and died. Though, of course, the two never married, they saw themselves that way. In a letter to Mary, Jane said, "There is reason in the habit of married folks keeping together.” Jane would write letters every day they were apart, saying things like "I miss you dreadfully and am yours 'til death." Without her, Jane seemed lost. She died just over a year later due to undiagnosed cancer.

While Hull House proper has not existed since the 1960s, a portion of it still exists as the Jane Addams Hull-House Museum. Years ago, the museum had a project called “Was Jane Addams a Lesbian?” The exhibit included letters from Jane Addams to her lovers. Jane Addams is a special case, in that we can say certainly that she was, even if she did not use that language. Jane Addams was inducted into the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in 2008 and the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display which celebrates LGBT history and people, in 2012. Despite this, there are still several scholars who advocate she was not a lesbian. One scholar, believes that we shouldn’t even consider whether she was a lesbian because it could “overshadow” the good she did. As if who she loved could erase all she did. She was a co-founder of the ACLU. She was the first American woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. She is considered the founder of social work in the US. Yet somehow, these things do not overshadow her work at Hull House. How we live, who we love, and what we leave behind work together to define us, and how they work together enriches each element. Jane Addams’ experiences were a vital part of her work, and when you remove one part, you lose the chance to fully understanding the others.

[Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material]

Addams, Jane, and Christopher Lasch. The social thought of Jane Addams. Bobbs-Merrill, 1965.

Addams, Jane. The second twenty years at Hull-House. Macmillan, 1930.

Addams, Jane. Twenty years at hull-house. University of Illinois Press, 1990.

Brown, Victoria Bissell. The Education of Jane Addams. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Bryan, Mary Lynn McCree, Barbara Bair, and Maree De Angury. eds., The Selected Papers of Jane Addams Volume 1: Preparing to Lead, 1860-1881. University of Illinois Press, 2002.

Elshtain, Jean Bethke. The Jane Addams Reader. Basic Books, 2002.

Michals, Debra. “Jane Addams.” National Women’s History Museum, 2017.

Paul, C.A. “Jane Addams (1860-1935).” Social Welfare History Project, 2016.