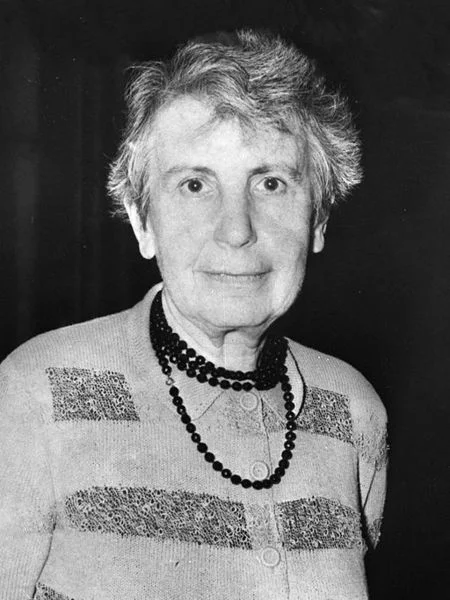

A black and white photo of Anna Freud wearing a sweater and necklace. She is looking at the camera, smiling slightly.

“I was always looking outside myself for strength and confidence but it comes from within. It is there all the time.” — Anna Freud

Anna Freud is not the most well-known name in the Freud family. Intentional or not, there is a heavy shadow hanging over her story. Sigmund Freud is a well-known man, but he is not well-loved in the queer community. His homophobic and transphobic ideas taint his already largely disproven theories. Worship him or despise him, he is well remembered and still discussed in most psychology circles. The same cannot be said for his youngest daughter. One of the founders of child psychology and an open lesbian, Anna Freud was not always in line with her father’s teachings. Despite all of the conflict one would expect between them, one fact is clear: Anna Freud loved her father.

Anna Freud remembered being different from her family, and the more one learns about her childhood the more sense that makes. It is often said that she was her father's favourite child, and this led to resentment from her mother and siblings. An often cited cause for this rift was a moment during a hike where Sigmund fell and hurt himself, and when everyone else got startled and ran away, Anna stayed and comforted him.

It is after this incident that he began inviting her into his workspace, allowing her to organize and even read some of his papers, letting her sit in during meetings with other famous psychologists. Her ability to learn from her father is most likely what sparked her later interest. The issue with this is that Freud made it clear that he had a favourite daughter—to both Anna and the rest of the family.

It was around the same time that Anna began to masturbate. The idea of women wanting to pleasure themselves, of wanting pleasure at all, was directly against the ideals of Vienna at the time. It was eventually decided that Anna was to go to a spa to "recover."

It was quickly decided that she had "hysteria," a diagnosis given to most women expressing unpopular traits. Symptoms of hysteria included anxiety, fainting, partial paralysis, irritability, lack of appetite for food, desiring sex too much, not desiring sex enough, “a tendency to cause trouble for others”, nervousness, heaviness in the abdomen, and amnesia.

Her sexuality became a hot topic of discussion that not only had her sent away but also destroyed her remaining relationship with her sister. She was kept at the spa for so long that she was unable to be present at her sister's marriage.

This discord came at a rare time of contention between Anna and her father. Though she worked hard to please him and, in many ways, followed in his footsteps, Sigmund decided she was following too closely. She expressed her desire to attend school and study psychology like her father, who didn't believe women should go to university. She conceded her point only when he suggested she become a teacher in order to study the effects of certain psychological practices on children.

During this time of conflict with her father, Sigmund reached somewhat of a conflict with himself.

One of Sigmund's beliefs about psychoanalysis was the inherently erotic relationship between patient and practitioner. He publicly denounced the idea of analyzing family members, as he believed it would be incestuous. However, when Anna turned eighteen, Sigmund began analyzing his daughter.

In only a short time, Anna Freud was diagnosed with hysteria, forced to give up her academic dreams, pushed into becoming a school teacher, and put into a situation with her father that he deemed inherently erotic. She adapted to each issue differently.

After having been called hysterical, she would take walks with her father in the hope that he would help her perceived ailment. She also dove deeper into her work. She worked as an assistant at a school and brought with her a new approach to psychology: she got down to their level and engaged with them in play.

Her sessions with her father, however, were strictly traditional. Her father asked his standard questions, probing into her sex life, her fantasies, and her dreams, seeking the meaning behind each. Freud was a man who was determined to fit facts into his theories, even saying:

“Having diagnosed a case, we may then boldly demand confirmation of our suspicions from the patient. We must not be led astray by initial denials. If we keep firmly to what we have inferred, we shall, in the end, conquer every resistance by emphasizing the unshakeable nature of our convictions.”

It is through these means that he made claims about his daughter and her sexual desires, which he eventually turned into a paper.

Anna later sat in the audience as her father read that paper to the public. Though he did not share her name with the audience, he did make it clear that he thought it unlikely that her case would end well, and it was unlikely she would ever be able to reach “sexual normalcy”.

This finally ended Anna's sessions with her father. Hurt and betrayed, she focused even more on her work.

Her father, on the other hand, began to focus on his older daughter who died shortly after.

With one daughter refusing to let him dissect her and the other dying, Freud followed Anna's lead and threw himself into work, dreaming up new theories and digging for anything that might prop them up.

Using her experience, Anna found work with Seigfried Bernfeld at a home for Polish children orphaned by war. She began to psychoanalyze the children, and this became her first proper step into the world of psychology. She was fascinated, but her own experiences made her cautious.

It was expected that she would eventually present a paper on her findings to the larger psychology community. When given the opportunity, she refused to present information on any of the children she had looked after. Instead, she presented a paper on herself, omitting her name and coming to a very different conclusion than her father had years earlier.

Shortly after, she met Eva Rosenfeld, a foster mother who took in one of the children that Anna assisted. Upon their meeting, Anna offered to stay and help with the children, including through psychoanalysis. The two began an affair and eventually fell in love.

Anna's father successfully ended the relationship when he began analyzing Eva and convinced her she was a heterosexual woman who needed to go back to her husband. This was not his first attempt in the realm of conversion therapy.

Anna was not free from this treatment, but she was able to escape her father's influences and found herself in a relationship with a woman named Dorothy Burlingham. Dorothy had been forced to flee America with her four children in order to escape an abusive husband. When she arrived in Austria, she went to the Freud family for shelter and support.

After much time, Anna essentially became a co-parent to Dorothy's children. She and Dorothy stayed together until Dorothy's death in 1979.

Before then, there were other things on the horizon. World War II was approaching, and the Freud family grew anxious as the Nazis gained power. The family was targeted for being Jewish, and Freud's controversial theories led to his books being burned.

It was Princess Marie Bonaparte that came to the family’s rescue. Marie was another queer woman who actively disagreed with many of Sigmund’s beliefs, but she helped the family escape Vienna. She moved them to England, where Anna began the next step in her career.

After the war ended, she and Dorothy opened the Hampstead War Nursery for children who had lost their parents or had otherwise been displaced by the war. It was through her work at the nursery that she took her characteristic hands-on approach, interacting and playing with the children while she studied them, learning more about the effects of stress and instability on children's mental well-being. Anna Freud began giving lectures on child psychology in London. In 1973, she was elected President of the International Association of Psychoanalysts.

Even after everything, she still loved her father. She nursed him when he became sick and often wrote fondly of him. This cannot excuse anything Sigmund Freud did, especially to his daughters, but it does give more depth of understanding to her choices.

Anna Freud advocated for children fiercely. Standing by the fact that not only should children be treated differently than adults, but they also needed to be given stable environments in order to thrive. She always tried to get on the same level as her patients, and remove as much of the power imbalance as possible without forgetting that she was dealing with children. She even said at one point:

“'With due respect for the necessary strictest handling and interpretation of the transference, I feel still that we should leave room somewhere for the realization that analyst and patient are also two real people, of equal adult status, in a real personal relationship to each other'.”

When she died in 1982 her ashes were placed next to Dorothy’s and her home was turned into a Freud museum according to her wishes.

While she loved her father, she was not him. She respected and admired him until the moment she died, but she was still a person outside of him, and even often in defiance of him.

[Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material]

“Adoption History: Anna Freud.” The Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, 2012, pages.uoregon.edu/adoption/people/AnnaFreud.htm.

“Anna Freud and Child Psychoanalysis.” Freud Museum London, www.freud.org.uk/learn/discover-anna-freud/anna-freud-life-and-work/child-psychoanalysis/.

Babits, Marty. “Remember Anna Freud?” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 2017, www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-middle-ground/201705/remember-anna-freud.

Perry, Susan K. “Anna Freud's Astounding Story.” Psychology Today, Sussex Publishers, 2014, www.psychologytoday.com/ca/blog/creating-in-flow/201406/anna-freud-s-astounding-story.

Sandler, Anne Marie. “Anna Freud.” Institute of Psychoanalysis, 2015, www.psychoanalysis.org.uk/our-authors-and-theorists/anna-freud.