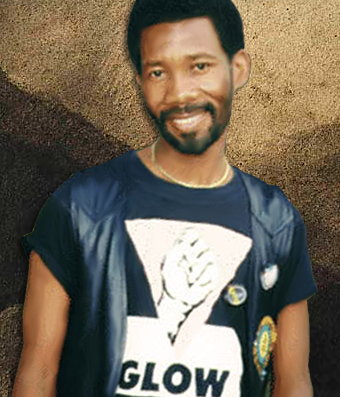

A full colour photo of Simon Tseko Nkoli smiling at the camera. He is wearing a vest with buttons on it.

“If you are Black and gay in South Africa, then it really is all the same closet…inside is darkness and oppression. Outside is freedom.”

— Simon Tseko Nkoli

Content warning for suicide

In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” as a way to describe her experiences as a black woman. It is meant to describe the complexity of experiencing multiple forms of marginalization and the ways in which multiple levels of oppression interact.

Born in 1957, decades before Crenshaw's Intersectionality Theory got its name, Simon Nkoli wouldn't have access to the term until much later in his life, if he learned it at all. That being said, Crenshaw, herself has said that the concept itself is not new. “So many of the antecedents to it are as old as Anna Julia Cooper, and Maria Stewart in the 19th century in the US, all the way through Angela Davis and Deborah King.”

The term is fitting to describe Nkoli's work and experiences with oppression as a gay, black South African living through Apartheid.

From a young age, he was aware of what it meant to be a black man in South Africa. Raised by grandparents who worked for a white landowner, he attended school in an attempt to find a way out. When his grandfather and the landowner demanded he quit school to work full-time on the farm, he ran away to live with his mother and step-father in Sebokeng.

It was then that he became involved in politics; he became a member of the Congress of South African Students and joined the fight against Apartheid. As he discovered his own sexuality, he found there were limits to his work. When he came out, Congress took a vote to decide if he could continue to serve. Though he was allowed to continue, there were repercussions.

While his family claimed support, they could not handle it. When Nikoli began a relationship with a white bus driver named Andre, there were protests from both families. Where Nikoli's mother protested because he was gay, Andre's mother protested because he was black.

His family's attempt to "cure" him meant bringing him to religious leaders who would quote anti-gay scriptures. When that failed, they brought him to a psychiatrist—a gay psychiatrist who, rather than try and dissuade him from his relationship, offered counsel and support.

It was only when Nikoli and his partner made a suicide pact that his mother finally offered the men her approval.

During this time, Nkoli also joined the Gay Association of South Africa (GASA). The group was primarily white and held the incredibly white stand of being apolitical. While Nkoli was heavily involved in the anti-Apartheid movement, the GASA refused to support him or discuss any of the race-related issues he brought up.

This came to a head when, during a rally for rent-boycott, Nkoli was arrested. He was among the twenty-one political leaders arrested in what was later called Delmas Treason Trial; all faced the death penalty if convicted. While in prison awaiting trial, his sexuality became public knowledge. His fellow prisoners demanded a separate trial, worrying that his sexuality would condemn the rest of them as it would him.

At the same time, the GASA was deciding whether or not to support Nkoli or allow him to stay in the group. While his fellow prisoners decided to stay on trial together, the GASA kicked him out and refused to support him.

Terror Lekota, another defendant in the Delmas trial later spoke of this experience:

"All of us acknowledge that Simon's coming out was an important learning experience…. How could we say that men and women like Simon, who had put their shoulders to the wheel to end apartheid, should now be discriminated against?"

In 1988, four years after his initial arrest, he was acquitted and moved on to found the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of the Witwatersrand (GLOW). GLOW learned from the mistakes of GASA, making sure to include black members in their leadership and support more than just white community members.

Nkoli also travelled extensively after his release, earning awards and visiting many other leaders, both queer and not. He was the first gay activist to meet with President Nelson Mandela. He was instrumental in making South Africa the first country to have gay rights enshrined in its constitution. It was in 1990 that he and Beverley Palesa Ditsie organized South Africa's first pride parade in Johannesburg. Nkoli said at this march:

"With this march, gays and lesbians are entering the struggle for a democratic South Africa where everybody has equal rights and everyone is protected by the law: black and white; men and women, gay and straight."

He later became one of the first gay men in the public eye to share that he was HIV positive. He founded Positive African Men based in Johannesburg and later died there due to complications from illness at the age of forty-one.

For most of Nkoli’s life, he faced a clear divide, and the people around him tried to make him choose which part of himself to be most loyal to. He refused to make that choice, saying:

"I am black and I am gay. I cannot separate the two parts of me into secondary or primary struggles…. So when I fight for my freedom I must fight against both oppressions. All those who believe in a democratic South Africa must fight against all oppression, all intolerance, all injustice."

Any person who stands at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities can recognize this struggle. It's not an easy one to manage, but it is that balancing act that made Nkoli the leader he was. He was the first in many regards, and he made room for the seconds, thirds, and fourths who came after him.

[Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material]

GALA. Till the time of Trial: The prison letters of Simon Nkoli. Retrieved from https://www.gala.co.za/resources/docs/Letters_of_Simon_Nkoli.pdf

Hoad, Neville Wallace. Karen Martin. Graeme Reid. (2005.) Sex and Politics in South Africa. Juta and Company.

Maglott, Stephen A. The Ubuntu Biography Project. Retrieved from https://ubuntubiographyproject.com/2017/11/26/simon-tseko-nkoli/

Martin, Yasmina. (October 2015). The GLOW Collection. Retrieved from https://www.gala.co.za/resources/docs/Archival_collection_articles/GLOW.pdf

United Democratic Front. Biography of Tseko Simon Nkoli. Retrieved from https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/biography-of-tseko-simon-nkoli-