Schubertiade Music & Arts [www.schubertiademusic.com]

“Besides Dalí, there was one other hero Friday night, Francisco Monción, who took the part of Tristan. He carried off the most acrobatically strenuous part without a flaw, and more than that he projected the character and the story convincingly. He is a very fine dancer indeed, and a quite exceptionally imaginative one.” – Edwin Denby

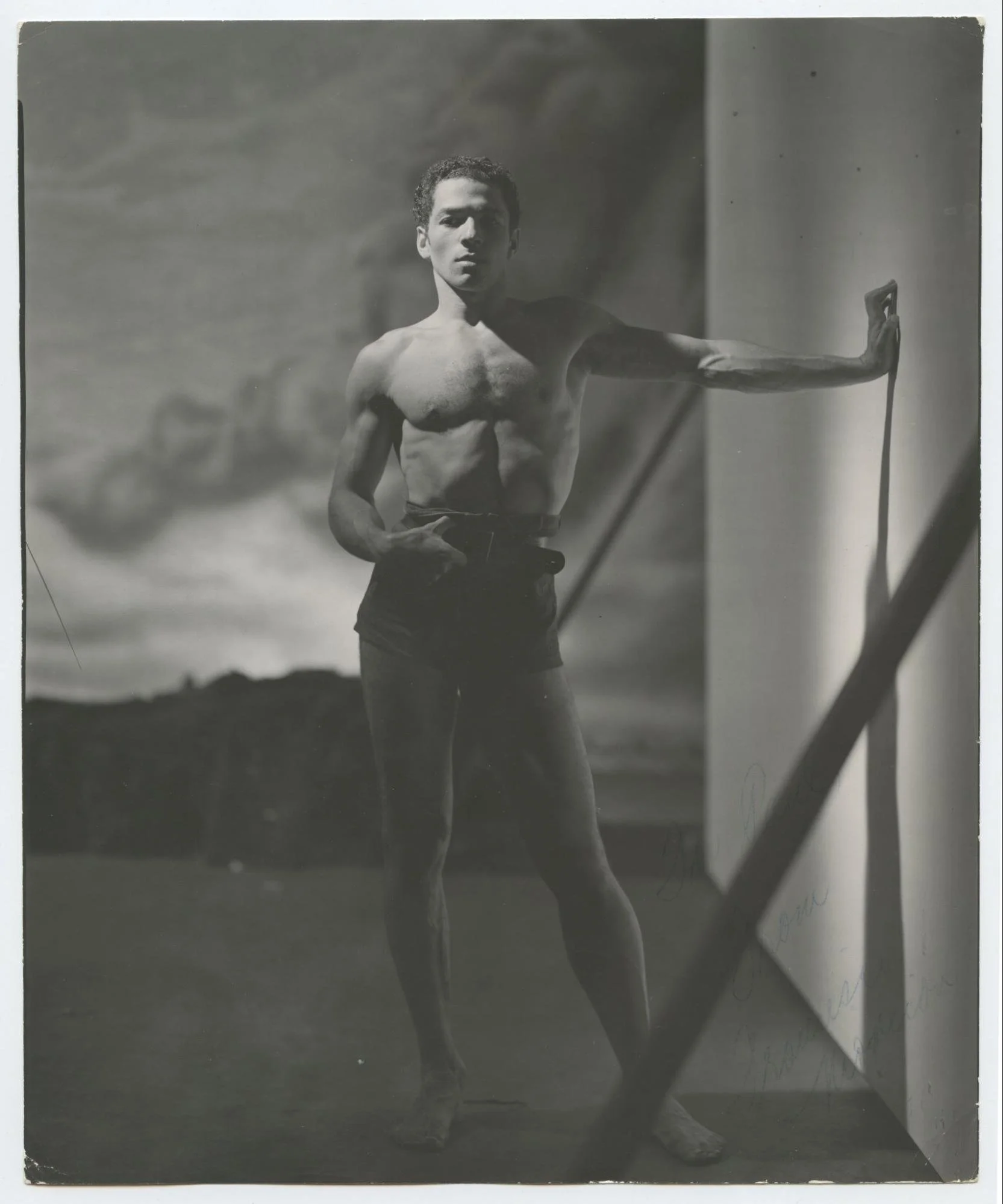

One of the more striking images to exist of Francisco Monción is a quietly erotic photograph of the dancer taken by the great George Platt Lynes, who during his lifetime amassed a substantial body of work of nude and homoerotic photography. In this particular photo, Monción stands shirtless, facing the camera head on, as he leans with one hand propped against a wall while his other rests, perhaps suggestively, atop the belt of his high-waisted shorts. His lean but muscular dancer’s build is lit unevenly, with varying patches of light and shadow rippling across his figure to reveal the veins and sinews of a thoroughly toned physique. In the lower right quadrant of the image, one can faintly make out that the photo is signed in ink: "For Paul / From / Francisco Monción."

It is this photograph and its personalized dedication, along with several other similarly homoerotic images taken by Lynes as well as Carl Van Vechten, that best reveal Francisco Monción’s presence in queer history. A quiet and eloquent individual, Monción’s demeanor in interviews comes off as humble and demure, and his social and romantic lives are hardly mentioned, if at all. His queer body is thus best documented for the world through the lives and lenses of other gay male artists who ran in his circles. Via photography, we know that Monción caught the eyes of Lynes and Van Vechten, two of the premier queer photographers collecting male portraits at the time. Via other narratives, we know that Monción had romantic encounters with other male dancers and choreographers during his career, including Nicholas Magallanes, Jerome Robbins and Lincoln Kirstein. But for the most part, what we know of Monción is not what he left behind in stories of his personal life or of his sexual conquests, but rather in his resume. A dedicated dancer, Monción spent decades racking up a substantial and impressive body of work, constantly honing his craft and expanding his repertoire. As a result, he is perhaps best remembered for becoming the New York City Ballet’s longest tenured principal dancer, and his name can be found across countless program bills and performance recordings.

Francisco Monción was born July 6, 1918 in Concepción de la Vega, a large city in the La Vega province of the Dominican Republic. At that time, the Monción surname was already well-known in the DR, as it was linked to the name of General Benito Monción, an army officer and war hero of French descent who fought in the Dominican Restoration War (1863-1865) which resulted in the restoration of Dominican sovereignty. Francisco’s family was connected to Benito, and his ancestors likely included Hispanics as well as French and Black Africans. Like most Dominicans, Francisco, or Frank as he would often be called for short, was consequently both ethnically and racially mixed.

When Francisco Monción was an infant, his father passed away and his family immigrated to the US soon thereafter. As he was growing up, his mother played the piano frequently and classical music had a regular presence in their home. Dancing was not exactly on Monción’s radar as an interest or possible career; he in fact had aspirations to become an aviation engineer and even began taking pertinent courses in the field. There are numerous rumors and stories, however, which collectively contribute to Monción's happenstance path towards dancing, which ultimately found him with a long career as a performer for the next half century.

In his youth, Monción was quite fit and active, and he engaged in sports and exercised frequently. According to one narrative, Monción remembers working out at the 63rd Street Y on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where he saw and was inspired by dancers who would stretch and practice there regularly. He recalls beginning to mimic the various moves and positions he saw them rehearsing, and recognized the ease with which the moves came to him. Already in his teenage years, Monción thus only began to pick up dance moves for the first time at a very late age for a male who would one day become professional.

From this same time period in his life, Francisco recalls another pivotal anecdote, involving Lincoln Kirstein. One day as a young teenager, Monción recollects that he was walking down the street minding his own business when an unknown man to him, later revealed to be Kirstein, the future founder of the New York City Ballet, passed him by and shouted, “Hey, kid, want to be a dancer?”

Monción also tells of a third inspiration, when he recalls seeing the film The Goldwyn Follies, a movie for which the legendary George Balanchine had choreographed two exceptional dance numbers. Monción watched the film at a time when he had been ruminating over what he wanted to do in life, and it rendered him infatuated with dance, and with Balanchine in particular. He soon discovered that Balanchine had an academy in New York, and wrote to it asking for a performance catalog. Around the same time, a friend of Francisco’s asked him if he was interested in studying dancing and recommended he go see a contact he had at the School of American Ballet. Tall, handsome, and with an obvious gift for movement and nothing to lose, Francisco soon presented himself at the School.

One way or another, in 1938 Monción was offered a scholarship to the recently established School of American Ballet, founded by the renowned Russo-Georgian-born choreographer George Balanchine, alongside Edward Warburg, and of course, Lincoln Kirstein. The school, which had only opened in 1934, had just begun recruiting male students at a time when few males in America were making their way into classical ballet. The School of American Ballet was looking to fill their roster, and so they accepted Monción as a scholarship student despite his dearth of experience. As a result, Monción only began professional dance training at twenty years old, an incredibly late age for any dancer to be starting out. Nevertheless, he immediately found himself in technique classes taught by the likes of accomplished dancers such as Pierre Vladimiroff, Anatole Oboukhoff, and Balanchine himself. Much like someone thrown into the deep end of a pool without knowing how to swim, Francisco was forced to adapt quickly.

While he was still a student, Monción made his stage debut only a couple years later in 1942, when he appeared as part of the ensemble in Balanchine’s Ballet Imperial, in a production staged at the Majestic Theater in New York City by the New Opera Company. With what would seem to be a dance career just about to take off, Monción then had to put performing on hold as he was drafted into the US Army, where he would serve for two years during the peak of WWII before being discharged and returning to New York.

For a short while, it looked as though Monción’s dance career would be completely sabotaged by the war, as he was discharged from the army after having developed spots on his lungs from a bout of pneumonia. Upon his return to New York in 1944, he worked hard to recover and with compromised health, Monción took on his first role as a professional dancer, playing a “gypsy” (likely due to his skin color) in a Broadway revival of The Merry Widow, Franz Lehar’s famous operetta. The dances in the show were choreographed by none other than Balanchine, who likely aided in getting Monción the part. The show would unfortunately close that same year.

Monción then joined Marquis de Cuevas’ Grande Ballet as a principal dancer and soloist. There he played the titular role in two major productions: Edward Caton’s Sebastian and Leonide Massine’s Mad Tristan, a Surrealist piece whose sets, costumes, and artwork were done by Salvador Dalí himself. Of the latter piece, dance critic and writer Edwin Denby wrote, "Besides Dalí, there was one other hero Friday night, Francisco Monción, who took the part of Tristan. He carried off the most acrobatically strenuous part without a flaw, and more than that he projected the character and the story convincingly. He is a very fine dancer indeed, and a quite exceptionally imaginative one.”

Between 1946 and 1947, Monción briefly performed with Colonel Wassily de Basil and René Blum’s Original Ballet Russe dance company. He then would make what would become his most career defining move, when in 1947 he signed on to become an original charter member of the Ballet Society, the dance company founded by both Balanchine and Kirstein that would be the predecessor to what became the New York City Ballet. 1947 was also a life changing year for Monción for another reason: it is the year he became a US citizen.

With the Ballet Society, Monción would go on to be cast in numerous experimental works such as The Four Temperaments and The Triumph of Bacchus and Ariadne. The Society became the City Ballet in 1948, and Monción spent the next four decades with the company, becoming its longest tenured principal dancer still listed on its roster through the spring of 1985. At the New York City Ballet’s first ever performance on October 11, 1948, Monción danced in all three ballets on the program, a true testament to the adulation that Balanchine and Kirstein had for him.

During his long tenure, Monción would originate numerous memorable roles and participate in countless historic performances, including playing Prince Ivan in Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird in 1949, the role of Death in Maurice Ravel’s La Valse in 1951, and The Boy in Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun in 1953. Though not necessarily the most technically perfected dancer, Monción became known throughout his dance career for his performance versatility, being highly adept at effectively portraying a breadth of characters via dance movement. He could just as easily exude mystery and sorrow while playing the brooding Dark Angel character in Orpheus, or play as comical and jocular in the humorous role of The Husband in Jerome Robbins’ The Concert.

Beginning in the ‘50s, Monción also began to experiment with choreographing his own works. In 1955, he collaborated with Balanchine and Barbara Millberg for The New York City Ballet’s Jeux d’Enfants. He then choreographed three more pieces on his own for the NYCB: Pastorale in 1957, Choros No. 7 in 1959, and Les Biches in 1960, as well as two pieces for other companies: the Honegger Concertino for the Pennsylvania Ballet in 1965 and Night Song for the Washington Ballet in 1966.

At the age of 65 (though he remained on the NYCB roster for two more years), Monción finally transitioned into a life of quiet retirement, where he would indulge his creativity by oil painting at his home in Woodstock, NY, even going as far as to showcase work in several New York exhibitions. Just over a decade later, Monción passed away on Saturday, April 1, 1995 from cancer, at the age of 76. At the time of his passing, it was revealed that Monción had established a scholarship fund to help promote dance training specifically for Hispanic youths. To date, the scholarship is administered by the Kaatsbaan International Dance Center in Tivoli, NY.

In his passing, Monción left behind not only a scholarship but also a legendary career, with an extensive list of roles he originated or made his own during his fifty years in dance. While he may not have been the most technically proficient dancer on stage at any given moment, Monción was time and again called out by reviewers and critics for his incredible character work in performances. Though he may have fallen into dance by chance, Monción’s legacy as a performer shows his remarkable ability to be a vessel for the artistic medium. As a performer, he allowed his own persona to be enveloped into each and every character he played and in that respect, Monción seems to have been the perfect fit for a dancer. A man absorbed in each role he took on, Moncion was able to showcase his true passion, allowing his own being to be consumed for the sake of others’ pleasure.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: some of the sources may contain triggering material

Fisher, Barbara. In Balanchine’s Company: A Dancer’s Memoir. Middletown, Wesleyan University Press, 2006.

Harris, Dale. “Balanchine's Pioneer: Obituary of Francisco Monción.” The Guardian, 1995, April 13. link.gale.com/apps/doc/A170632158/AONE?u=nysl_oweb&sid=sitemap&xid=02fd2429

Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library. "Interview with Francisco Monción, 1979." The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1979 - 1979. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bb507740-3b72-0134-3056-60f81dd2b63c

Jowitt, Deborah and Jerome Robbins. Jerome Robbins: His Life, His Theater, His Dance. New York, Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Kisselgoff, Anna. “Francisco Monción, 76, a Charter Member of New York City Ballet.” The New York Times, 1995, April 4. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1995/04/04/466095.html?pageNumber=90

Leddick, David. Intimate Companions: A Triography of George Platt Lynes, Paul Cadmus, Lincoln Kirstein, and Their Circle. St. Martin's Press, 2000.