“It is the abolition of the ‘manly’ and the ‘womanly.’ Will you not help to sweep them into the museum of antiques?”

– Eva Gore-Booth

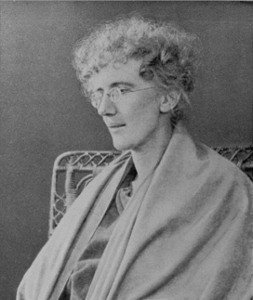

Coining the term “Sex is an accident”, Eva Gore-Booth was faced with an uphill climb in her lifetime in the early 20th century. A poet, suffragist, and lifelong activist, her story is sometimes forgotten in the shadow of her more famous sister Countess Markievicz who had many of the same aims of gender and class equality. Eva found her path through her partnership with Esther Roper, her lover and lifelong companion.

Raised by the 5th Baronet in the Lissadell house in Ireland, Eva was born on 22 May 1870. From a young age, she was raised with the belief that a part of having privilege was helping the people who didn’t; with her father feeding people through the Irish Famine, and her mother establishing a school of needlework for women in Lissadell. With her four siblings, she was quick to learn about the inequalities in the world, and like many of her siblings, she learned to fight against this inequality. Esther Roper would write of Eva’s early life that Eva was“haunted by the suffering of the world and had a curious feeling of responsibility for its inequalities and injustices."

Early in life, Eva and her writing would be noticed by fellow poet W.B. Yeats who would mentor Eva, hoping for her to become a great Irish poet. She had the opportunity to travel the world with her family, knowing five languages and keeping journals of her time moving through different countries. It was when she fell ill in Venice that she would slow down and end up visiting an olive grove where she first met Esther Roper. Eva would write a poem about their first meeting:

“Was it not strange that by the tideless sea

The jar and hurry of our lives should cease?

That under olive boughs we found peace,

And all the world’s great song in Italy?

You whose Love’s melody makes glad the gloom

Of a long labour and a patient strife,

Is not that music greater than our Life?

Shall not a little song outlast that doom?”

Their relationship would develop relatively quickly, with Esther writing:

“For months illness kept us in the south, and we spent the days walking and talking on the hillside by the sea. Each was attracted to the work and thoughts of the other, and we soon became friends and companions for life.”

It is here, with Eva and Esther’s relationship, where the controversy starts. Like many queer people in history, their story is often twisted and turned to find an interpretation that isn’t romantic. Specifically, as Sonja Tiernan recorded, one of the early touchstone biographies of the two women was written by Gifford Lewis, who said this to the Gore-Booth family:

“You will be pleased to know that I could find not a trace of perverted sexuality—they [Eva and Esther] actually had a campaign—complete with journal—to persuade people to abandon sexuality altogether.”

It is clear from this letter that the biography is biased in the favour of wanting there to be no romantic relationship between the two women. In a paper responding to the biography, Sonja Tiernan concluded:

“To ignore or willfully misread evidence in relation to Eva Gore-Booth in order to imply—or in Lewis’s case insist—that Eva was heterosexual is an example of how homosexuals are written out of history. Lewis’s argument is futile; she attempts to disprove that Eva was a lesbian when the facts of her life, love, and literature all prove otherwise. Lewis’s assertions in relation to Eva’s sexuality are at times contradictory, misleading, and lacking evidence.

The quest to prove that Eva Gore-Booth was heterosexual is another way of contributing to the bigoted system of presumed heterosexuality. This system breeds homophobic attitudes that exclude non-heterosexual people from our history books. When evidence suggests that individuals were homosexual, that evidence has often been manipulated or misread in order to prove those individuals were heterosexual. Through the system of presumed heterosexuality, the dominant group are historicized as the discoverers, artists, writers, and the people who mattered, while the activities of marginalized groups are ‘not merely unspoken, but unspeakable.’”

The argument of lack of sexuality can be cut through as well, with Emma Donoghue writing:

“If our ongoing debates on the meaning of sexuality are to make any sense, it is crucial that historians stop conflating the sexually active/celibate distinction with the lesbian/heterosexual one. Whether Eva and Esther were celibate and calm in their feelings, celibate but impassioned, occasionally sexual, sexual early on and then “transcending” it, or discreetly sexual right through their relationship, the fact of their lifelong lesbian partnership remains.”

The idea of celibacy comes specifically from a queer publication called Urania that Esther and Eva had a part in founding along with Irene Clyde, Dorothy Cornish, and Jessey Wade. The founders included many different flavours of queerness, among them a transgender woman, and the publication reflects that; discussing the idea of love between women, gender confirmation surgery, queer people from history, and radically bucking against gender essentialism from 1916 to 1940. With that context, it seems far more likely that any discussion of celibacy comes not from the angle of their relationship being entirely without a sexual aspect and platonic but instead from an inclusion of romantic relationships without a sexual component. In modern language, isn’t it much more likely that the very queer publication was simply including people on the asexual and aromantic spectrum as divinely queer before those words were widely available?

Either way, these women, who fought to recognize Sappho as a lesbian, who were friends with fellow queer vegetarian Edward Carpenter, and who lived together for almost their entire adult lives, had queerness deeply embedded in their lives. To remove that is to remove a dimension of not only them as people but of the worldview that informed their lifelong activism. Considering their rejection of gender essentialism, their constant fight for suffrage for women is contextualized. Also, their relationship with each other was an important part of both of their lives.

Eva was diagnosed as being close to death before meeting Esther, and it was through their connection they were able to recuperate from their concurrent illnesses. After only three years of knowing each other, Eva would make Esther the sole beneficiary of her will, and Esther is largely credited for radicalizing Eva’s politics. One of the closest people to Eva, Countess Constance Markievicz, had clear thoughts on their relationship, writing after Eva’s death, she was, “so glad that Eva and [Esther] were together. So thankful that her love was with Eva until the end”

Their connection not only contextualized their partnered work in activism but also Eva’s writing. Emma Donoghue wrote that Eva’s poetry “appropriated linguistic and poetic conventions, as well as Celtic mythology, to feminize and lesbianise the stories handed down to her”.

The two would stay together until Eva’s death at 56 on 30th June 1926 from cancer. She had kept her illness from her sister in an attempt to shield her. Esther died on 28 April 1938 after spending much of her time after Eva’s death writing about Eva and her sister and building their legacies. Eva and Esther were buried together, and on their grave is a quote from Sappho: "Life that is Love is God".

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING

Disclaimer: Some of the sources may contain triggering material

Byrne, A. (2019, May 22). EVA GORE-BOOTH / Suffragist, Trade Unionist, Poet, Mystic—. https://www.herstory.ie/news/2019/5/22/eva-gore-booth-suffragist-trade-unionist-poet-mystic

Eva Gore Booth | Lissadell House Online. (n.d.). Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://lissadellhouse.com/eva-gore-booth/

Eva Gore-Booth (https://www.poetryfoundation.org/). (2023, December 3). [Text/html]. Poetry Foundation; Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/eva-gore-booth

Frances Clarke. (2018, December 10). Eva Gore-Booth: Poet, mystic, trade unionist and suffragist. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/eva-gore-booth-poet-mystic-trade-unionist-and-suffragist-1.3719601

Gilbert King. (2012, July 10). Daughters of Wealth, Sisters in Revolt | History| Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/daughters-of-wealth-sisters-in-revolt-1319484/

Jill Mountford. (2021, March 1). Esther Roper, Eva Gore-Booth and “Urania” | Workers’ Liberty. https://www.workersliberty.org/story/2021-03-01/esther-roper-eva-gore-booth-and-urania

John Simkin. (1997, September). Eva Gore-Booth. Spartacus Educational. https://spartacus-educational.com/IREgorebooth.htm

Sonja Tiernan. (n.d.). Eva Gore-Booth—Herstory Ireland’s Epic Women | EPIC Museum. Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://blog.epicchq.com/eva-gore-booth-herstory-blazing-a-trail