“I can tell a story and I try to tell my whole feelings--the touch, the smell, and feelings. All I’m afraid of now is being like a few other guys I know who took photographs. When they die, maybe the family comes in and sees all this work they can’t do anything with, and they just shove it into the garbage. I want people to see these photographs and say ‘this is something from my time.’”

– Alvin Baltrop

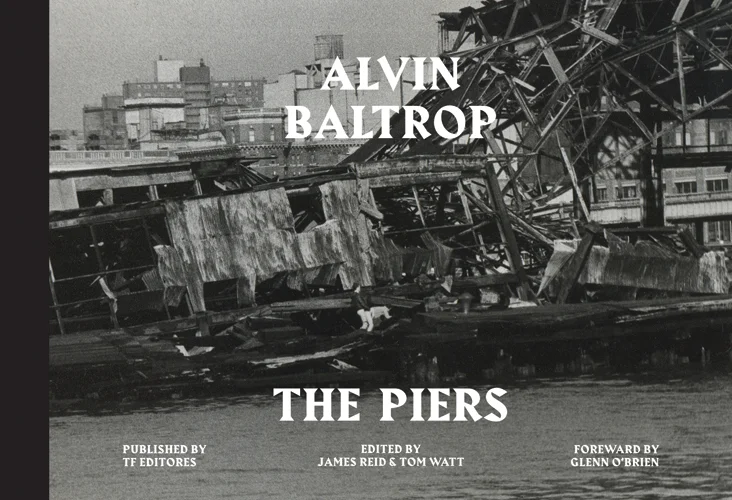

While sexual fluidity flourished during the 1960s, 70s, and 80s in the United States, artists across the country explored and documented the growing visibility of the LGBTQIA community. Many of these artists’ names are familiar like Robert Mapplethorpe, David Wojnarowicz, and Peter Hujar but black and brown artists like Alvin Baltrop have often been excluded from these narratives. Baltrop documented New York City’s abandoned Lower West Side waterfront from 1975 through 1986 in his best-known series The Piers.

Alvin Jerome Baltrop was born December 11, 1948, to Dorothy Mae Baltrop shortly after she had moved from Virginia to the Bronx with her eldest son James. He began photographing with a twin-lens Yashica camera gifted by his uncle when he was seventeen years old. Thereafter, Baltrop photographed New York with a style in the vein of Weegee and Helen Levitt. He documented Malcolm X rallies and the Stonewall Inn, the soon-to-be infamous bar that the photographer frequented when he was underage. His earlier photographs have been likened to the aesthetics of Roy DeCarava and reflect his inclination to play with light. He attributed this to his admiration of the lighting in 1930’s American cinema, like The General Died at Dawn and early Japanese films that utilized concentrated light. Sadly, his mother threw out most of his early photography so there are few images that remain.

Baltrop went on to join the Navy in 1969 at twenty years old before the Stonewall riots occurred. He remained closeted for his first year of service out of fear of the possible repercussions. The Stonewall uprising occurred while Baltrop attended boot camp, but he received news clippings about the events from friends. After his first year in the Navy, the photographer began to ask fellow sailors to pose clothed and nude for his images. Baltrop described his time in the Navy as such:

“I was a medic. They called me W.D.—witch doctor. I built my developing trays out of medic trays in sickbay; I built my own enlarger. I took notes about exposures, practices, techniques and just kept going. I think I perfected my lighting skills. Later, working in a commercial photography studio I learned timing and how to frame a photograph in your head.”

The blatant racism that existed in the Navy is quite apparent by the nickname given to Baltrop, “witch doctor”—conveniently ascribed to the black medic. Being called W.D. foreshadowed the racism he would face in the years to come when he attempted to display his photography within the New York art world. Even still, his statement exemplified the self-awareness of his artistic talents. Baltrop actively refined his craft while in the Navy and further developed his understanding of photography in the years following his service.

He was sent home to the Bronx with an honorable discharge in 1972. Baltrop went on to attend the School of Visual Arts in 1973 and left the program in 1975 to become a taxicab driver. He would drive to the Lower West Side piers on his breaks and photograph the city’s abandoned waterfront. Mafia crackdowns and the migration of manufacturing to New Jersey and Brooklyn in the 1950s and 1960s left the piers abandoned for years. Their vacancy enabled the occupation of the waterfront by artists, drug users, queer persons, transgender folks, and sunbathers.

Baltrop credited his girlfriend, Alice, as someone who encouraged him to keep photographing the piers from the start of the series in 1975. He and Alice would continue dating until they broke up in 1980. Baltrop went on to meet his future partner of 16 years, Mark, at the piers on the same night of their separation. He would go on to care for Alice and Mark until both their deaths from complications of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.

There is ambiguity surrounding the photographer’s sexual orientation. Valerie Cassel Oliver called him bisexual in “Alvin Baltrop: Dreams into Glass.” Others like Douglas Crimp, Robert F. Reid-Pharr, and Randal Wilcox did not comment on his sexual orientation. Osa Atoe criticized the tendency for writers to label Baltrop bisexual and claimed that he preferred to be called homosexual. Due to the limited resources available to him and their conflicting insights, it is difficult to determine who is correct on this matter. He will be referred to as a queer artist going forward as to say that he was not straight, but this is not to say that he identified this way in his lifetime.

Shortly after he began The Piers series, he quit his taxicab job and bought a van so he could camp out at the piers for extended periods of time. He would attach a makeshift harness to warehouse rafters so that he could take his aerial photographs and other more voyeuristic compositions.

Spending nights, days and even weekends at the piers, Baltrop developed relationships with the individuals he photographed and those who frequented the piers. He photographed colorful murals by David Wojnarowicz but claimed that he did not know Wojnarowicz at this time. Alvin Baltrop identified artists who frequented the piers and even developed relationships with some of them. Peter Hujar was part of this scene and photographed the piers. He captured artists like Wojnarowicz amid sexual acts set against a backdrop of murals by Tava and Keith Haring. Haring, Hujar, and Wojnarowicz stand today as prominent figures in the East Village art community, artists who Baltrop likely would have crossed paths with over the eleven years he spent making The Piers series. Baltrop was aware of Wojnarowicz, but they were not friends.

In his attempts to tell the story of the New York piers, Baltrop captured a visual ethnography of the people, warehouses, water-front, murals and sculptures at the piers. The queer men immortalized in Baltrop's work display a range of body types that broke the monotony of the overly muscled men prevalent in the queer imagery of the time. As the AIDS epidemic plagued global communities in the 1980s and 1990s, many of the people shown in these images would sadly pass away. In this way, Baltrop developed a visual history of the Lower West Side piers and its gradual decline throughout the 1980s until its ultimate demise in 1986 all while memorializing the innocent lives lost during the AIDS epidemic.

The Lower West Side piers acted as a hub for many artists, many of whom have been exhibited and discussed often, like David Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, Leonard Fink, Tava, Vito Acconci, James Baldessari, Gordon Matta-Clark, Harry Shunk and Jean Kender, all white men, as well as Shelley Seccombe, a white woman. The piers were a muse for writers like Andrew Holleran, John Rechy, and Edmund White. While these artists and their works from the piers are readily discussed, Baltrop has often been written about as a tertiary character or only in brief.

In The History that Alvin Baltrop left Behind, Randal Wilcox, a dear friend of the late, artist wrote that Baltrop had a difficult time exhibiting The Piers during his lifetime. Baltrop is quoted in this piece, saying that his portfolio was met with an “evil response” where a woman likened him to a sewer rat. Wilcox elaborated that gallery owners doubted that Baltrop could have taken these photographs, with one curator asking if he had stolen a white photographer’s artist portfolio. Meanwhile, those who were responsive to his photography were said to of attempted to steal it and sell it as their own. After these racist experiences, Baltrop grew to distrust galleries and opted to paste poster facsimiles of his work throughout Manhattan as a means of democratic exhibition.

As a result of his blackness and queerness, Baltrop was not widely shown during his lifetime. He had a solo show in 1977 at the Glines, a gay non-profit, and once at a gay bar in the East Village where he was a bouncer. Otherwise, galleries that would traditionally display homoerotic works were not receptive to his photography. Baltrop’s pier photographs were on display for a time at the Bar in New York in 1992. His artwork was featured on the cover of Art Forum four years after his death in 2008 for “Douglas Crimp on Alvin Baltrop.” His photography was exhibited at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, Fotomuseum Winterthur, and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía after Crimp’s 2008 article in Artforum.

Alvin Baltrop depicted New York’s Lower West Side waterfront and the people who frequented it from the perspective of a community member. His images take pride in the queer sexualities of the subjects shown, while also capturing moments in history that were otherwise overlooked in favor of white artists working at and documenting the piers. His artwork stands today prominently among his contemporaries. His experimentations with light and his raw, diverse survey of the cruising, graffiti and sunbathing hub that was New York City’s Lower West Side piers, are unique and rich with cultural value. As such, Alvin Baltrop must be recognized for his contributions to queer history and be brought out from the shadows of white gay male oppression.

Bibliography

Altman, Lawrence K. “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” New York Times. July 3, 1981.

Anderson, Fiona. "Cruising the Queer Ruins of New York's Abandoned Waterfront." Performance Research. Vol. 20, no. 3 (2015): 135-144.

Atoe, Osa. “Alvin Baltrop: A queer Black photographer’s groundbreaking work comes to life five years after his death.” Colorlines. March 24, 2009. http://www.colorlines.com/articles/alvin-baltrop.

Baltrop, Alvin J., James Reid and Tom Watt, eds. Alvin Baltrop : The Piers. Madrid: TF Editores, 2015.

Barnard, Ian. Queer Race: Cultural Interventions in the Racial Politics of Queer Theory. Gender, Sexuality, and Culture. Vol. 3. New York: Peter Lang, 2004. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip0410/2003022438.html.

Bianchi, Tom. Tom Bianchi: Fire Island Pines, Polaroids 1975-1983. Bologna: Damiani, 2013.

Bianchi, Tom. “Fire Island Pines - 1975-1983.” Accessed May 2, 2017. http://tombianchi.photoshelter.com/gallery/G0000JCF8JQ6a79U.

Cooke, Lynne, Douglas Crimp and Kristin Poor. Mixed Use, Manhattan: Photographs and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2010.

Crimp, Douglas and Adam Rolston. AIDS Demo Graphics. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1990.

Crimp, Douglas. "DISSS-CO (A FRAGMENT) from ‘Before Pictures, a Memoir of 1970s New York.’" In Criticism 50, no. 1 (2008).

———. Douglas Crimp on Alvin Baltrop. Vol. 46. New York: Artforum Inc, 2008.

Cunningham, Nijah. "A Queer Pier: Roundtable on the Idea of a Black Radical Tradition." Small Axe 17, no. 1 (2013): 84-95.

Fernandez-Sacco, Ellen. “Check your baggage: Resisting whiteness in art history.” Art Journal. Vol. 40, no. 4 (Winter 2001).

Hirsh, David. “Piers: Alvin Baltrop, the Bar, 2nd Ave. at 4th St. April 17-May 8.” New York Native. 1992.

Kramer, Larry. Faggots. New York: Penguin Books USA Inc., 1978.

Lax, Thomas J., Jeannine Tang, A. Naomi Jackson, Parallel Lines, Ginger Brooks Takahashi, and Marvin J. Taylor. "Queer Pier: 40 Years." Art Journal 72, no. 2 (2013): 106-113.

Reid-Pharr, Robert F. “Alvin Baltrop.” The Piers from Here: Alvin Baltrop and Gordon Matta-Clark. Liverpool: Open Eye Gallery, 2013. 44-57.

Oliver, Valerie Cassel. "Alvin Baltrop: Dreams into Glass." Callaloo 36, no. 1 (2013): 65-69.

Oliver, Valerie Cassel, Douglas Crimp and Randal Wilcox. Perspectives 179: Alvin Baltrop: Dreams Into Glass. New York: Distributed Art Publishers, Inc., 2010.

Weinberg, Jonathan. “City-Condoned Anarchy.” The Piers: Art and Sex along the New York Waterfront. New York: Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, 2012.

Wilcox, Randal. “The History That Alvin Baltrop Left Behind.” Atlántica: Journal of Art and Thought. Vol. 52, Spring/Summer 2012.

Wojnarowicz, David. Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

About the author

Michael J. Carroll is an art historian pursuing his masters at Temple University who lives and works in Philadelphia, PA.